Southern Cameroons Nationalism: From CATTU to SCACUF (2004 to 2017)

By Wilfred Tassang*

Prison Principale, Yaoundé, La République du Cameroun

(The story as narrated with scintillating, nauseous, and hitherto unheard-of details by an eye witness)

The English System of education in Southern Cameroons has suffered regular and persistent attacks from the centralized government in Yaoundé. Over the years, Southern Cameroonians have had to run street battles with security forces, suffered broken limbs, imprisonment and deaths to protect a system they considered far superior to what Yaoundé wanted to impose on them. Unknown to them, something worse than evil was happening in that same system unchecked until 2004. It was in the summer of that year that the leadership of the Cameroon Teacher’s Trade Union, CATTU, (a union dedicated to the well-being of teachers and to the protection and preservation of the Anglo-Saxon system of education) discovered that learners in their technical colleges were being taught in French, Pidgin or a street language called Franglais and that this had discouraged parents from sending their children to public technical schools. In July 2004, CATTU stumbled on a Baccalaureate Technique examination paper in Motor Mechanics wherein candidates were asked to: “Give the functions of a candle in the engine of an automobile.” It was an examination set for Francophone learners by French-speaking teachers, poorly translated and imposed on English-speaking candidates. The advocacy to get answers and solutions to this problem plunged the syndicate head-on into the seething Southern Cameroons Nationalism.

The more the unions sought solutions to this problem, the more it became clear that the two systems and peoples could not live together. We persisted still but failed because Yaoundé was bent on completing their project of assimilation.

The advocacy for higher teacher training colleges and, for a second Anglo-Saxon university that started in 2004 took CATTU and UPTA (Union of Parent-Teacher Associations) first to the Presidency of La Republique du Cameroun, and to the Prime Ministry in 2005, and in 2007. The advocacy only started yielding fruits in 2009 after five years of resistance. In March of that year, a union delegation led by Nkwenti Simon met with the LRC Higher Education minister threatening the holding of an All Anglophone Conference on Technical Education, which conference the minister was told, had the potential to degenerate. The outcome of that threat was a promise to expand the then ENS Annex Bambili, ENSAB, to include technical education disciplines while waiting for President Paul Biya to create the institutions officially, at his leisure. This was meant to be a deception but, the union pulled a fast one on Minister Jacques Fame Ndongo; we got Ambazonians working at CRTV to announce the promise to create on CRTV 3 pm News and on Morning Safari the next day. It earned John Mbah Akuroh a disciplinary suspension but, Yaoundé could no longer renege on that promise. The union further engineered motions of support to Paul Biya from CPDM Section and Sub Section presidents in order to force his hand on this matter. “That was how low we stooped to get what we wanted for our children”, said Nkwenti Simon later. This tied Fame Ndongo’s hands to his promise but, it opened the door for even greater challenges with the system as the erstwhile covert efforts at assimilation now became brazenly overt even on Southern Cameroon’s soil.

The recruitment of both student teachers and lecturers in the newly created technical departments of ENSAB testified to this. More than 90% of the students recruited in the purely technical disciplines were Francophones while 100% of lecturers were French-speaking. The Cancer attacked general education disciplines as well. Challenged, the authorities declared that “Anglophones did not write the entrance examination.” That of course was a lie. Southern Cameroonians who applied to teach in the institution, some with terminal qualifications, and others working towards the obtention of the same but who were told vacancies did not exist testified to the union. This situation continued to crescendo even after President Paul Biya created the Higher Teacher Training College and, the Higher Technical Teacher Training College. The faculties of the newly created university were flooded with Francophones to the extent that one was appointed Deputy Vice-Chancellor in Charge of Academic Affairs. Inconceivable, but it happened.

In 2011, the Union decided to seek higher political solutions. The outcome of a seminar-workshop it organized on the subject in Buea was the call for the holding of an Estates General on education, otherwise called National Education Forum, the outcome of which the union hoped, would be a clear demarcation of the two cultures and systems of education. That was in August 2011. The then Prime Minister, Philemon Yang granted this request promptly in September of the same year. In 2012, he convened the Estates-General for 2013 and charged the Minister of Higher Education to oversee its organization. Against all expectations, Minister Fame Ndongo ignored the orders of the Prime Minister and vehemently refused to meet with the unions to discuss the matter. Instead, in 2013, the Minister of Secondary Education, Louis Bapès Bapès, attempted another assault; he signed a decision suppressing core science subjects (Biology, Chemistry, and Physics) from the lower classes of Secondary Education in a bid to francophonise the English system of education. It took a combined CATTU and TAC visit to the Etoudi palace to wade off this assault.

In 2013, it had become clear that the union alone could not get solutions to the problem; recourse had to be made to the larger community of stakeholders. The National Executive Secretary-General of CATTU (yours humbly) set out on a territory-wide tour to inform and educate stakeholders in all the divisions (Counties) on the stakes and challenges of the day. The reaction of parents and teachers as his team combed the territory showed that they understood the stakes and the times, and much more, they agreed on the needful; an indefinite strike action if it came to that.

The deployment of student teachers on the field for practicum was making the situation very glaring for all to see. In 2014, a Francophone, Cameroonese History student teacher in GBHS Bamenda taught her students that “the 11th of February was the date of the Annexation of Le Cameroun Occidentale by Le Cameroun Orientale.” In another class, a Biology student teacher was asking the students to “sweep the blackboard.” The carnage was on. Students spent the better part of these lectures giggling, that is, for those who bothered to sit in.

In September of 2015, the principal of GBHS Down Town Bamenda, Mr. Nkwenti Patrick, refused to send French-speaking student teachers to practice on English-speaking learners. That earned him an unending series of summonses and persecution by the colonial administration and security services; he stood his grounds and the union-backed him up. The student teachers were withdrawn from his institution but the genocide continued in other schools unperturbed. The situation had degenerated.

In December of 2015, a joint delegation of CATTU and TAC succeeded to meet with Minister Jacques Fame Ndongo in Bamenda. At the end of that late-night meeting, the unions resolved to block the practicum of Second Cycle student teachers from Bambili because, in reply to the grievances, the Minister declared boldly that Cameroun was a bilingual country; anybody could teach in whatever language they wanted anywhere. He even threatened to bring LRC constitutional experts to defend this crime. Students returned home for the festive holidays with flyers informing them and their parents that schools would not resume for the second term until the Francophone student teachers were withdrawn. Panicked, the colonial governor stepped in. He convened a meeting of stakeholders to look into the issues. At the end of two days of lengthy and drawn out discussions with the authorities of the University of Bamenda and the two teacher training colleges on the one hand, and the CATTU, TAC, and parents, on the other hand, it was resolved that the university should withdraw the student teachers under contention and redeploy them to the Francophone sections of the bilingual colleges in Mezam for secondary general education, while those for technical education would be posted to Francophone technical colleges out of the Southern Cameroons. Strangely but not surprisingly, the Vice-Chancellor and the directors of the training colleges refused to sign the agreement that would have set them at loggerheads with Yaoundé. The colonial governor himself developed cold feet and rather, instructed his Secretary-General, Monono Absalom to sign on their behalf.

Fortunately for the unions, Minister Fame Ndongo had invited them for a meeting on the 4th of January 2016 in Yaoundé. At the union’s insistence, the Minister of Higher Education co-chaired the meeting with his counterpart of Secondary Education. At the end of the meeting, it was agreed among other issues as follows:

1. That French-speaking student teachers would no longer carry out practicum on English-speaking learners.

2. That all French-speaking teachers already teaching English-speaking learners subjects other than the French language would be withdrawn by the Minister of Secondary Education.

3. That the Prime Minister would set up an inter-ministerial commission to proffer lasting solutions to the now perennial problems of Anglophone education.

The colleges of education did withdraw the French-speaking student teachers before schools resumed for the second term. The Minister of Secondary Education, on the other hand, did not keep his part of the bargain. According to Minister Jean Ernest Ngale Bibehe, technical colleges would not have teachers if he withdrew the Francophone teachers. Worse, in August of 2016, the ministry posted more French-speaking teachers to English-speaking schools. Confronted on the matter during the beginning of year meeting, Minister Bibehe informed the union that he could not fabricate English-speaking teachers. He deploys what the Ministry of Higher Education sends to him, he said. Higher Education had only Francophones to send because that was all they recruited for training. It was at this point that the union reached the point of no return.

The National Executive Council of the CATTU took the decision to shut down the education industry in Southern Cameroons until we had lasting solutions. It was thus time to seek and build alliances and partnerships with trade unions within and out of the Public Service. Trade unions in the French system of education refused to support the cause, while private and confessional sector trade unions in the Southern Cameroons readily came on board, as parents first, and then, as teachers. The University of Buea Chapter of the Higher Education Syndicate didn’t have to be convinced. They came on board readily. The University of Bamenda Chapter of the syndicate, infested with Francophones, refused to join. Accosted, the business and transport sectors readily came on board to protect the education of their children. Even at this juncture, we kept on exploring ways and means to get the solutions needed so that we could avoid the strike action; we wrote to and met with Church leaders, virtually begging them to intervene. We wrote to leading Southern Cameroonian political leaders within the Colonial ruling CPDM party such as Simon Achidi Achu and Peter Mafany Musonge. We met with Chairman Fru Ndi on the matter. For the first time, we got leading CPDM and SDF members to discuss together an issue that concerned their people. We assumed nothing and left nothing to chance, yet, Yaoundé was stubborn and adamant. That stubbornness I believe, is of the Lord.

We are in September 2016, and the Prime Minister still had not created the inter-ministerial commission the ministers promised he would. Thousands of more new French-speaking teachers had been posted to English system colleges to unteach the children, to discourage them, and keep them away from both public general and technical colleges.

On the occasion of World Teacher’s Day, October 5, 2016, the teacher’s unions acting in unison, informed Colonial Governor Lele l’Afrique that the strike action suspended in January would resume without prior notification if the earlier grievances were not completely addressed by the state. Taken unawares, Governor Lele l’Afrique danced on three legs. He made a mockery of the unions and said the state could neither be threatened nor intimidated.

By the end of the month, the teacher’s unions proclaimed November 21 as the date for the start of an indefinite shutdown of the education industry across the territory. Yaoundé took it for granted. The system had been accustomed to foiling trade union strikes through bribery and corruption and thought this too would go the same way. It mistook purely political demands for what it called “des revendications corporatistes”, syndicate or professional grievances. It was God that blinded them.

By November 15, 2021, trader’s and driver’s unions waded in to support their children and teachers. They issued strike notices. Then November 21 happened; teachers stayed home as planned, students stayed home. The markets were closed and township taxis were grounded in solidarity. Francophone students who wanted to go to school were intimidated by the ghosts walking the streets. Parents who had not withdrawn their children from boarding schools did that after the ghosts left the streets on November 23rd. Yet, Yaoundé took it for a joke. They said we would get tired and return to school; “Ils finiront par rentrer à l’école”, said LRC Government spokesman, Issa Tchiroma Bakary. By the end of two weeks, it dawned on Yaoundé that it was a serious matter after all.

Even then, Yaoundé’s first reaction was denial and defiance and then attempted to sabotage. The Central Committee of the colonial ruling CPDM party dispatched two prime ministerial delegations to Buea and Bamenda to tell the people that the teachers’ unions were lying and that they had no problems. The two delegations led by former PM Peter Mafany Musonge to Buea and Philemon Yang to Bamenda met with resistance. The youth whose future the system had ambushed came out to resist them. The confrontations in Bamenda on December 08 2016 led to five deaths, the first being Julius Akum. Blood had been spilled, the tree of freedom had been watered again with human blood. The blood of these children and the thousands who have died after them has not stopped asking for justice. It will not stop until the homeland is set free.

By December 2016, it had become clear to Yaoundé that a semblance of talking was needed. The Prime Minister finally created the promised inter-ministerial commission to look into the grievances. Typically, he placed it under the chairmanship of Jacques Fame Ndongo, the same Minister whose government department created the problems in the first place and who had unashamedly told the unions in December 2015 that Cameroun was a bilingual country and so, teachers could teach in whatever language they chose, irrespective of the learners, their grades and disciplines. The teacher’s unions refused to turn up and requested a change of both the chair of the commission and the venue. The opposition to the venue was informed by the incivilities and physical humiliation visited by Common Law lawyers in Buea and Bamenda earlier in November 2016. If these could happen to lawyers on their home turf, how much more would Yaoundé do to teachers, the unions feared. Security was at risk.

The tension kept rising across the territory and a load of grievances kept increasing. By the time the Prime Minister himself descended from his very highly exalted pedestal to meet with the unions in Bamenda in late December, the Consortium had been formed. The Prime Minister refused to receive the Consortium as a body. He met with the various components thereof differently, but all were unyielding. It was during the meeting with teachers and parent’s unions that Mr. Yang declared that “the government could not withdraw French-speaking teachers from English speaking classrooms” because according to him, that action would “disturb social cohesion,” whatever that meant to him. The unions informed him that social cohesion had already been disturbed by what Francophones were doing to unsuspecting learners, but the PM would not be moved. The negotiations ended on the second night with the Prime Minister promising to create within 48hrs, a new structure for negotiations that would meet in Bamenda. The conditions that the unions gave him to motivate them to suspend the strike were not met. Instead of announcing special recruitment of student teachers of Southern Cameroons origin, the PM ordered the recruitment of 1000 bilingual science and technical teachers. This was interpreted to mean the recruitment of more Francophone teachers seeing that there was no college where bilingual science and technical teachers were trained in La Republique du Cameroun. Consequently, the new inter-ministerial Ad-hoc Committee met amidst the raging school shutdown.

During the negotiations, the system wanted to make it appear like the Southern Zone had no issues with its assimilation plans and schemes. It was in trying to execute this plot that the Prime Minister’s office deliberately omitted Southern Zoners from the first session of the Ad-hoc Committee in Bamenda. We refused to be divided then and staged a walkout. We refused to be divided then; we will not be divided now that we have come this close to freedom.

What happened after the 2nd Ad-hoc Committee aggravated the situation. Yaoundé had no plans to execute the outcome of the negotiations. All they cared about was the strike suspension. To frustrate the struggle thereafter, there was a plan to eliminate the Executive Secretary-General of the Union, TASSANG Wilfred, and to blame his death on Southern Cameroonians who supposedly, would have been disappointed with him for “selling out.” “This much, I, TASSANG Wilfred learned from the Colonial Military Prosecutor in SED upon our arrival thereafter the Nera Hotel abductions. He wanted to know why I escaped. I told him my life was in danger and reminded him of the January 13 assassination attempt on my life and the arrest of Balla and Fontem. He said it was my people who wanted to kill me. I asked him why my people would do that seeing that I was working for them? Or was that what Yaoundé had planned to tell the people after my death?” Major Thaddée was Military Prosecutor in Bamenda at the time of the strikes and negotiations and certainly spoke of what he knew. Unfortunately for Yaoundé, the unions decided to follow due process before any suspension could be contemplated. The outcome of the negotiations must be presented to the various instances of the unions and to the people in popular Town Hall meetings for their approval before strike suspension.

As God would have it, Yaoundé forgot to pull out the ambush squad that it had put in place to eliminate Mr. TASSANG. Consequently, three bike riders were gunned down that night. A convoy of bike riders and a car was mistaken for his as it happened the previous night, whereas he had been delayed in the Governor’s office by Chairman Fru Ndi and Barrister Bernard Muna, (late). The reaction of the Consortium was to call for a two-day ghost town in protest. This meant that the scheduled meetings could no longer hold. Confused and frustrated, Yaoundé banned the Consortium and the SCNC and withdrew from the negotiations. Orders were given to arrest Consortium leaders. Barrister Agbor Balla and Dr. Fontem Neba were precipitated picked up by the Colonial Governor in Buea before the time given by Yaoundé. Alerted, Mr. TASSANG Wilfred went underground and subsequently, escaped to Nigeria in February 2017. It was from Nigeria that on behalf of the Consortium, he firmly endorsed the restoration option. A gathering of Frontline independence restoration movements met in Nigeria in late February 2017, and SCACUF was birthed. The people had come together and no matter what happened and is happening, the restoration drive is unstoppable.

As we commemorate October 1, 2016, Ambazonia should take stock. It is time to calculate our losses and to project where we would have been if our education system did not suffer multiple ambushes from Yaoundé. The decision to rise up to possess the possession of our children was the right thing to do, and that, we cannot pull away from. Not after coming this close, not after 400+ villages and communities razed to the ground, not after more than 30,000 deaths.

The situation that awaits us if we fail to realize this dream is much worse than you can imagine. La Republique presently has as many of its citizens as can and will fill all the positions in Ambazonia. This time, they will be doing so as “Anglophones” not Francophones. Don’t we already have them in the public service, in government, in the private sector, “speaking for us?” Francis Wete, Felix Mbayu, Mimi Mefo? These are only the tip of the iceberg. The worst lies ahead for our children and their generations if we fail to deliver.

Ambazonians should therefore not be misled by unionists passing around for federalists. Federation is not an option to be considered. How can anybody dream of eating their dog’s vomit? Does it make sense to ask for that which Yaoundé said in 2016 was inconceivable and even up to now is not pretending to concede to? Should we fight, die, suffer exile and imprisonment only to be accepted as second-class citizens? We are not cursed.

Ambazonia cannot give up. We must not give up on the future of our children. If we do, tomorrow shall not be as clement on us as she was with Foncha. We are the educated and learned, the doctors and experts, the lawyers and economists, the political scientists, and all you can name that Foncha, Muna, and Endeley were not and did not have.

No. We CANNOT fail, we must not FAIL. We have GOD with us.

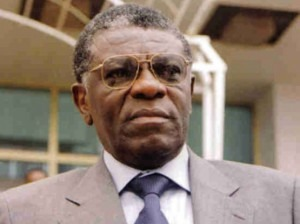

TASSANG Wilfred

Prison Principale, Yaoundé

La République du Cameroun