Cameroon: Recurrent Fighting Further Endangers Country’s Wildlife Resources

By Che Azenyui Bruno*

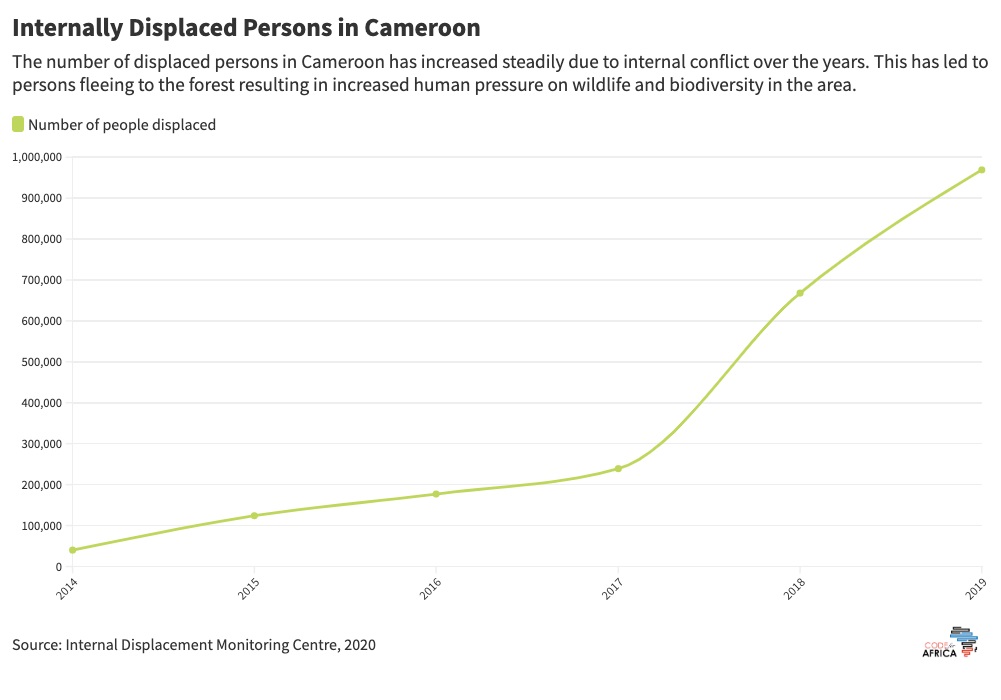

For the past five years and more, the two English-speaking regions of Cameroon have been the centre of a prolonged armed conflict that has reportedly claimed the lives of more than 30,000 persons and left hundreds of thousands internally displaced. Armed fighters from the country’s North West and South West regions are seeking secession, citing marginalization and attempted erosion of anglophone culture among other grievances.

A local human rights group, the Centre for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa, estimates that more than 4,500 persons have been killed in the current crisis rocking the country’s English-speaking regions.

While urban cities like Buea, Bamenda and Limbe have witnessed less intense fighting in the past five years, most rural and semi-rural communities have recorded intense and fierce confrontations between armed groups and elements of Cameroon’s defence forces, pushing large population groups to flee into the bushes and forest zones to seek refuge.

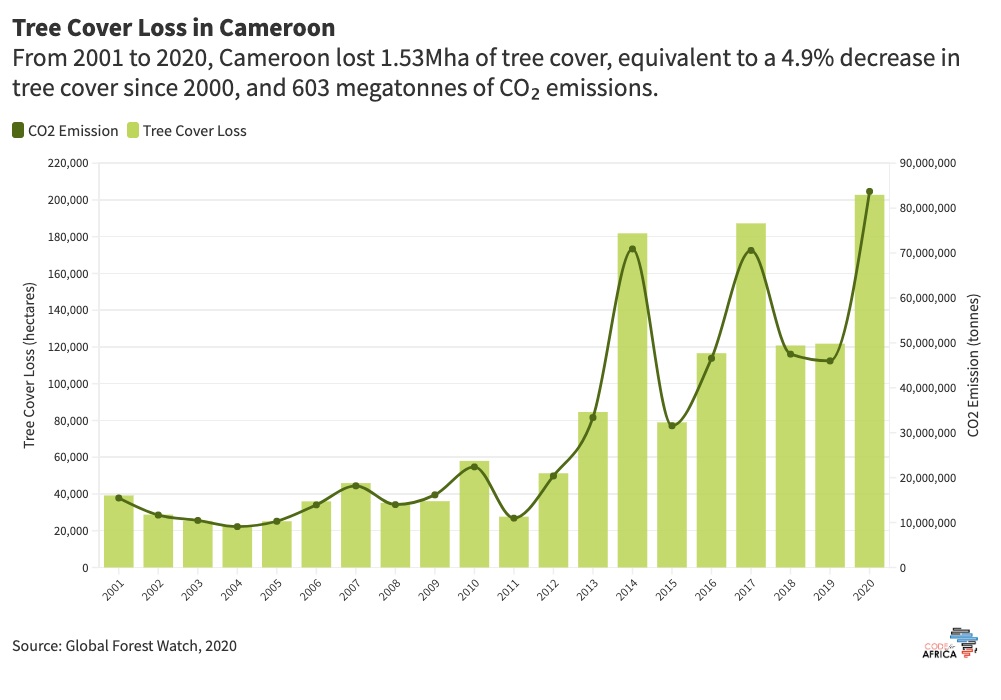

According to the international conservation group Global Forest Watch, in 2020 Cameroon lost 201kha of natural forest, equivalent to 83.0Mt of CO₂ emissions. The organization further reports that from 2001 to 2020, Cameroon lost 1.53Mha of tree cover, equivalent to a 4.9% decrease in tree cover since 2000, and 603Mt of CO₂ emissions.

The Environment and Rural Development Foundation (ERuDeF), a conservation non-profit in Cameroon, reports that the fighting has sent more than 90% of the population of Lebialem division in the South West region fleeing into forests, resulting in increased human pressure on wildlife and biodiversity in the area. The effect of this mass displacement, ERuDeF states, has been the large-scale conversion of animal habitats into makeshift human settlements and the poaching of protected wildlife species for food.

“Most conservation activities in the Lebialem Highlands have been totally halted so that conservators, village forest management committees, local rangers and eco-guards face difficulties in carrying out their activities. Some activities have been completely quarantined in the area,” a recent ERuDeF report states.

The Lebialem Highlands is one of several conservation hotspots in the South West region that host some of Cameroon’s treasured and endangered wildlife species like Cross River gorillas, forest elephants, chimpanzees and other endemic primates.

Other biodiversity hotspots in the North West and South West regions have also been ravaged by the conflict, one for which many believe there is no ready-made solution in sight.

ERuDeF Cameroon reports that more than 14 biodiversity hotspots in the North West and South West regions have been affected by the armed conflict plaguing the two regions. The effects of the crisis on biodiversity, it says, range from encroachment into protected areas by fleeing refugees and armed groups, setting up of fighter camps, indiscriminate killing of wildlife for food, destruction of forest cover for construction of makeshift settlements, attacks on conservation workers by fighting groups and discontinuation of livelihood initiatives in adjacent communities due to rising insecurity.

Samuel Ngueping, Landscape Officer of the Bakossi National Park in the South West region, recounts that since the onset of the current crisis they have barely been able to cover as much as 40% of their projects initiated within the 34 villages that make up the park.

“The Bakossi National Park currently spreads across 34 local communities in the South West region. Within the past four years, we have only been able to access about 20 of these 34 villages, the rest are simply inaccessible as a result of increasing security concerns,” Ngueping said.

“This puts wildlife and other forest resources in the park at risk, especially as we have concerns about poachers taking advantage of our absence to resume wildlife hunting within the protected areas of the park,” he said. “We also have strong reason to believe that most of the villagers fleeing the fighting into the bushes are indiscriminately destroying forest cover for residential purposes.”

Bakossi is one of 20 wildlife reserves that make up Cameroon’s biodiversity richness. Other biodiversity hotspots include the Bouba Njida, Takamanda, Mount Cameroon National Park and the Banyang-Mbo National Parks, and the Limbe Wildlife Sanctuary.

At the Mount Cameroon National Park Service, the head of unit for collaborative management, Ekomey Nelson, said less than 30% of the park’s activities within its protected areas and its adjacent communities are still in operation.

“Before 2016 we had operations in 41 communities that make up the periphery of the Mount Cameroon National Park and these activities were coordinated by village forest management committees composed of inhabitants of these villages. The situation has rarely been the same in the past five years. Less than 30% of our project sites are even accessible now as a result of insecurity,” he said.

Nelson was optimistic that most communities adjacent to the Mount Cameroon National Park are gradually becoming accessible. “Most members of our village forest management committees are beginning to return to the villages and our conservation activities are gradually resuming,” he said.

Longsi George Ngwa, conservator at the Banyang-Mbo Wildlife Sanctuary in the South West region, said almost all his eco-guards had fled their project sites as a result of escalating fighting between armed groups and defence forces in the area.

“Our conservation office was set on fire and almost all our eco-guards were forced to flee the area for safety. Most of the community members were relocating to other regions as a result of increasing insecurity. Virtually all 34 communities adjacent to the sanctuary were affected by the crisis,” Ngwa said, adding with optimism that activities are fast resuming in almost all villages adjacent to the sanctuary.

With a surface area of more than 66,200 hectares, the Banyang-Mbo Wildlife Sanctuary hosts most of Cameroon’s wildlife species classified by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as critically endangered, including the Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee and the black-bellied pangolin.

At the Limbe Wildlife Centre in the South West region, a notice at the entrance to the Centre states that the Centre had been closed to visitors for more than eight months. Enquiries indicated however, that the closure was in connection with prevention measures against Covid-19 and had nothing to do with the current crisis in the two English-speaking regions of the country.

* Che Azenyui Bruno is a Cameroonian development journalist and social entrepreneur. He is a former staff member of the Centre for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa, and is founder of Digifarms Africa.

This story was supported by Code for Africa and Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism, and was funded by the Global Forest Watch (GFW) with support from the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment (KLD). GFW supports data-driven journalism through its Small Grants Fund Initiative. The publisher maintains complete editorial independence over the stories reported using this data.